Let me talk about the new Deezer logo

I like design, and I wish I knew more about it. But, I'm not a designer.

Having said that, I don't know how fair it would be for me to talk about Deezer and their new brand identity, officially announced on November 7th — even knowing that I felt like talking about it, anyway.

Some background

I understand that Deezer is not as popular as Spotify or Apple Music. They are a French digital music platform founded in 2007, available in at least 180 countries and offering 120+ HiFi music tracks. But, the thing is, although they had 9.4 million subscribers and a revenue of € 450 million back in December, 2022, they most likely don't have the same brand recognition their competitors have.

By the time Deezer was released here in Brazil, back in 2013, I was a Spotify user, mostly because me, too, wanted to try the novelty of a digital music platform having only experienced MP3 downloads to that point, and because I lacked other options — I remember using a VPN to signup for Spotify, as they weren't available in Brazil until 2014 (me, pausing the writing, to notice that, OMG, Deezer came to Brazil before Spotify, even though Spotify launched in 2006, one year before Deezer).

The next year, 2014, Deezer made a partnership with TIM, which is, to this date, my mobile carrier of choice. From the moment their partnership started, I could listen to as much music as I wanted using my 3G, later 4G, later 5G, without being charged for any traffic and without having to pay for a separate subscription. That, together with Deezer Flow, an intelligent, AI-powered, algorithm able to provide me with better suggestions of music I would love to hear the more music I listened to, closed the deal for me. I chose Deezer and I never looked back (and, along with some other Deezer adopter friends, had unnumbered discussions about Flow and its undeniable powers that almost led to friendship ends).

Deezer visuals

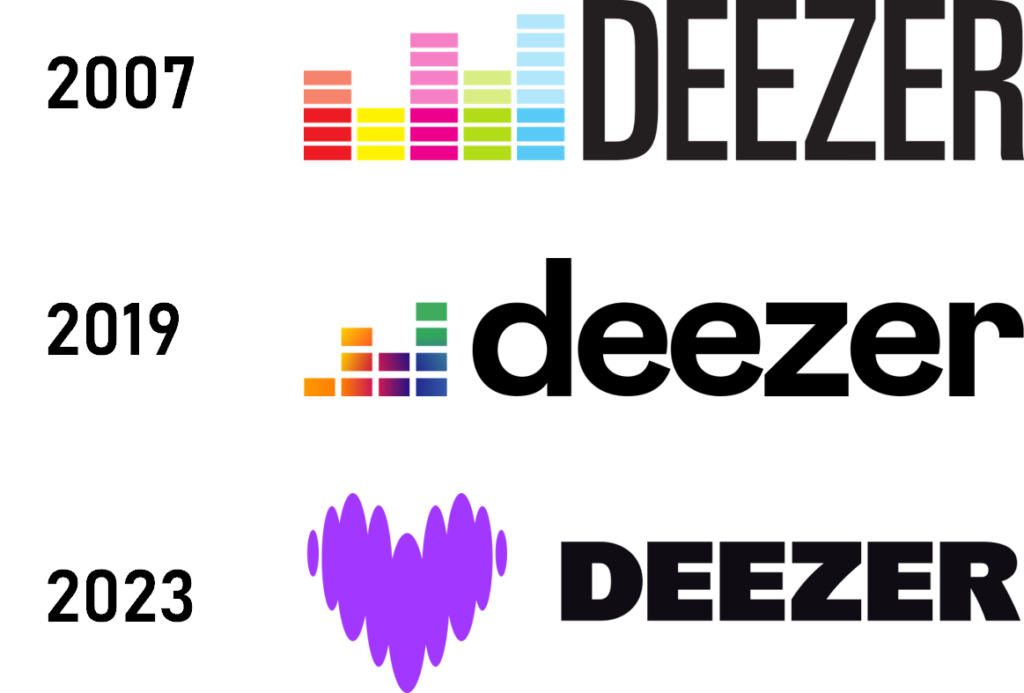

Having said all that, I never thought Deezer visuals was a winner. I mean, look at the image I created by stitching together their logos, all taken from Wikipedia for reference. Their logo, for a start, has always been horrible, at least in my humble opinion. But, you know, there are those services that you keep using despite of their visual design because they exceed in their offer, and that's fine.

Past 2019, I even learned to like their new logo. Got used to it.

So this week, when the totally unaware me saw a totally different logo on my iPhone's home screen, I thought... what?? The colorful equalizer had gone, replaced by a heart. A purple. Heart. I didn't understand until I read their press release:

Paris, November 7th, 2023 – Deezer (Paris Euronext: DEEZR) is reinventing itself as an experience services platform, with expression and connection as guiding principles to help artists, fans and partners to be and belong through music. To highlight the transformation and recharge people’s emotional connection to the brand, Deezer is refreshing its visual identity.

So their heart is here to express this new experiences and belonging feelings. Understood. But this didn't rid me of the immediate feeling I had: it really looked to me, at first site, that tapping that new icon would open a dating app (apparently, I'm not alone in this sensation). But with design, I'm learning there's always a reason, and Deezer's press release explaining the sense, I started imagining an animated version of the logo, pumping to the different beats of some music. Until I saw that Koto Studio, responsible for the brand redesign and Deezer's new design system, had thought about the same:

Moving on, there's their new font. Named Deezer Sans, again according to Koto Studio, it is “a variable font designed in close collaboration with the NaN type foundry”, which uses forms “directly inspired by the shapes within the logo”. The way I personally understood it is that some curves and shapes of the letters came from the beating heart logo. I believe that would be a cool thing to do, if I was a designer.

I saw people mentioning that this new font looked like the font used in Fortnite. I don't know about that, so I asked my younger son, who's played his share of the game, just to understand, from him, that there's no similarity. Besides, with variable font weights and combined with different applications, I really liked the results, although I don't think I would apply the font to any project of mine...

Finally, Deezer has come from a colorful logo to adopting a single color for its services and interfaces: purple.

I understood that they want their users to start associating purple to the brand, the same way one associates Netflix with red, Crunchyroll with orange and Spotify with green. Although I liked the move, because I do believe that, with time, people will indeed start making this association, I guess I'll be missing the colorful mix that was present in their logo and interface so far. In a sense, I believe the multiple colors helped demonstrate a mix of styles, of rhythms, of different people... I don't know. I'll just miss it.

I guess that's it. I really felt like speaking about this Deezer move. To be perfectly honest, my first impulse was to criticize it, but that was just because I hadn't had the time to stop and understand the change.

I guess that, as it happens with so many human areas of work, it's easier criticizing someone's work is easier than stopping to breath and understand before speaking your mind. I'm glad I could do it, so what I ended up doing (or, at least, tried to do) was to pay some tribute to the change, even if maybe my opinion.

I really hope this new Deezer interface thrives, and I wish it is long lived.

On subscriptions... with ads

So I was reading an entry Manu Moreale wrote about subscriptions, specially streaming services ones, and I have to say that I completely agree with his general opinion.

Subscriptions are getting a lot more expensive these days. So much so that I have decided to calculate how much I'm personally spending with them. And although I don't have these figures quite ready now and this will make for a future post, there are some highlights from his post I'd like to comment.

The issue with streaming platforms—but also with subscriptions in general—is that there’s a finite amount of people who are going to subscribe to a specific service. Which is fine if the goal is to run a sustainable business. As long as you’re pulling in more money that you’re spending, you’re good to go.

This is such a simple truth that it is worth repeating it.

For any given service, the amount of people subscribing to it will eventually come to a maximum. Be it because of the competition that'll make some people choose alternatives, be it because every consumer possible has already been reached and subscribed to the service, or anything else. There's really nothing wrong with it, as long as it's a sustainable business model one is after, as Manu says. When I was young, for instance, I remember my parents subscribing to a monthly Disney comic books package, which arrived at home for my reading. I didn't think about it at the time, but it's certain it wasn't every family in Brazil, where I live, that subscribed to the same package, or to any package at all, and yet the publishing house business model survived for years and years, relying on who had interest in the service. It lasted until the end of the comic books heyday around here.

But the problem, as Manu puts it, is that companies aren't after sustainable business models. Growth is their goal, even if they cannot grow forever. And as they cannot grow forever, they start doing weird things like charging extra fees for when your family members are watching something using your account but not in your residence's address (yes, Netflix, I'm looking at you). Or they increase their prices. Or both — not to mention when prices increase while the service offer decreases, like when a plan that used to offer 4K streaming starts to offer only FHD streaming.

There’s also another option, and it’s the one we’re seeing slowly creeping in at the moment: subscriptions plus advertising. Because you know what’s better than getting your money? Getting your money AND advertisers’ money at the same time.

This is the worst. And yet, Manu is as right as it gets. Because... why not? Here in Brazil, Netflix recently started offering plans with ads. They are cheaper, so it kind of justifies the ads (at a rate of 4 to 5 minutes of advertisement every 60 minutes), but if tomorrow or next week Netflix, or HBO, or Disney, or whoever decides to change their mind and include ads during the programming, who could stop them?

And then, there would you have it. Enshittification meets streaming services as much as it is already the case with retail giants such as Amazon.

I wish I could change the channel.

Querida mamãe

Esta semana terminei de ler "Make it Stick", de Peter C. Brown, que aqui no Brasil, graças às fabulosas traduções que são pensadas pelas editoras, ficou com o título de "Fixe o conhecimento". Falando sobre técnicas e a ciência da aprendizagem, o livro me interessou porque, como o tema lifelong learning me atrai bastante, imaginei que haveriam bons insights que eu poderia obter com a leitura.

Como em vários livros de não-ficção, o autor vai intercalando os conceitos que apresenta com histórias e relatos diversos que comprovam ou demonstram suas explicações. E uma dessas histórias, sobre o escritor americano John McPhee — considerado um dos pioneiros da não-ficção criativa —, me chamou a atenção.

Falando sobre bloqueio criativo em um artigo seu para a revista New Yorker de 2013, John McPhee disse que "escrever, como qualquer forma de arte, é um processo iterativo de criação e descoberta". Disse também que muita gente que aspira a escrever não consegue se expressar por não ter a "certeza do que querem dizer, não conseguem mergulhar no assunto".

Na revista, ele supõe estar escrevendo sobre um urso pardo. Só que depois de olhar para a tela por seis, sete, dez horas, nada lhe ocorre, nenhuma palavra aparece. É quando aparecem o bloqueio, a frustração e o desespero. Mas McPhee tem uma solução.

Quando ele enfrenta a falta de inspiração ou a falta de criatividade impede que ele continue criando, ele simplesmente escreve uma carta pra mãe dele.

Escreva, ‘Querida mamãe…’. E então conte pra sua mãe sobre o bloqueio, a frustração, a inépcia, o desespero. Você insiste que não foi feito pra esse tipo de trabalho. Você choraminga. Você faz birra. Você descreve por alto o seu problema, e menciona que o tal urso tem uma cintura de um metro e quarenta e um pescoço de uns 76 centímetros, mas que poderia correr nariz-com-nariz com o Secretariat. Você diz que o urso prefere se deitar e descansar. Que o urso descansa catorze horas por dia. E você continua assim por quanto tempo você conseguir. Daí você volta e deleta o ‘Querida mamãe…’ e toda a choradeira e birra, e fica só com o urso.”

Tradução livre que fiz do artigo Draft No. 4, de John McPhee, na New Yorker em 2013.

Achei genial isso de escrever uma carta para minha mãe. Porque em parte eu imagino que isso elimine de fato certas barreiras criativas e certas pressões que existem no ato de escrever. Barreiras que eu, que nem escrevo direito mas que gostaria de escrever mais, fico colocando e criando para mim mesmo. Barreiras que escrevendo uma carta para a minha mãe, eu posso transpor.

E para quem fizer isso, McPhee sugere que há luz no final do túnel. Segundo ele, o mais difícil mesmo é terminar o primeiro rascunho. O primeiro rascunho é sempre mais demorado e se desenvolve de forma desajeitada, porque cada frase que se escreve afeta todas as demais, não importa se vieram antes ou se virão depois. Ele cita que a primeira versão de um texto seu sobre geologia da California levou cerca de dois anos para ficar pronto. Mas que a segunda, terceira e quarta versões, juntas, levaram seis meses. E que essa proporção de escrita de 1 para 4 é consistente no caso dele, mesmo que ele perca apenas alguns dias no primeiro rascunho. Isso se deve ao fato de que, ainda segundo ele, há diferenças de fase para fase e que depois da primeira fase vencida, é quase como se uma pessoa completamente diferente assumisse o trabalho. O medo de continuar a escrever desaparece e os problemas, quaisquer que sejam, tendem a se tornar menos ameaçadores e mais interessantes. A experiência ajuda mais, como se nosso lado amador fosse substituído por um profissional tarimbado. Será mesmo?

Para saber, acho que só mesmo seguindo o conselho dele e enfrentando meus próprios ursos.

How many things do you pay twice for?

Only recently I was able to come across a very interesting article, discussing that everything you buy actually needs to be paid for twice, otherwise that’ll be wasted money — and that this should be a finance lesson taught to anyone in school.

And I couldn’t agree more, even though this made me reflect very deeply on how many things I buy but don’t pay the second price for.

There’s the first price, usually paid in money. This is the usual price you have to pay if you wish to gain possession of whatever that is that you desire to have, be it a book, a new software or a game.

But the thing is, only after we pay the second price will we see any return on the first one. And this second price consists of all the initiative and effort required to gain its benefits — a price that could prove to be much higher than the first one.

In that sense, I quote this passage from the article:

A new novel, for example, might require twenty dollars for its first price — and ten hours of dedicated reading time for its second. Only once the second price is being paid do you see any return on the first one. Paying only the first price is about the same as throwing money in the garbage.

I had never in my life seen things this way. This has made me feel bad and terrible ever since, because — taking only books as an example — I have bought many, many, many of them during my life yet I haven’t had time to read half… no, a quarter of them, and this is all my fault. I know I have linked this post many times here, but, yes, tsundoku. That is an addiction, and maybe I’ll have to live and deal with it, because I love books, even those I haven’t read yet, although bought.

But wait, there’s more. After reading this one article I stopped to think how many streaming services I pay for monthly, even yearly, only to go weeks in a row without watching a single movie or series episode. How many online courses have I bought at Udemy, Coursera or the likes of them, without ever finishing them — without ever starting some. How many games did I buy in Steam and never played (the number would have you scared) only because I thought it would be a good idea to take advantage of their semiannual sale, never finding the will to start a single match.

This is me examining my own conscience aloud. This is a public confession, where I state that I should do different from now on: enjoy what is there to be enjoyed, yes, but cancel services, subscriptions and recurrent expenses whenever although paying for them I’m unable to reap the full benefits because the time to pay for the second price never comes, never presents itself.

I hope I can remember this self analysis later in my life and then be able to say that I’m paying twice for more of the things I wish to possess.

Have you ever considered this? Have you been paying for your acquisitions twice?

Cookies, esses monstros da internet

Foi em 1994 que o engenheiro da computação Lou Montulli, da Netscape, inventou o cookie. A partir dessa invenção as páginas web ganharam a capacidade de se lembrar de nossas senhas, preferências, configurações de idioma e várias outras informações relevantes.

Quem não gostaria de fazer compras com um assistente ao seu lado, escutando nossas preferências e segurando nossas sacolas enquanto andamos pela loja e escolhemos o que queremos, não é mesmo? Os cookies de Lou viabilizaram essa possibilidade, ou seja, a invenção em si foi revolucionária ao estabelecer a gravação de blocos de dados localmente — isto é, no dispositivo em uso pelo usuário enquanto ele acessar o site — para recuperação posterior, ou seja, em uma visita futura do mesmo usuário a este site. Tudo isso, então, configurava uma troca privada de informações entre usuário e site.

Mas menos de dois anos depois, as empresas que comercializam anúncios descobriram como hackear os cookies para uma função muito menos nobre e invasiva: rastrear o comportamento dos usuários. Estes novos cookies do mal começaram a ser chamados de cookies de terceiros, ou third-party cookies, em contraposição aos first-party cookies originais, que trocavam dados apenas entre usuário e site. Os cookies do mal são como aquelas escutas que são plantadas em filmes de espionagem: captam tudo o que está sendo feito pela vítima, mas só compartilham estas informações com seus aliados. Os espiões podem colocar seus cookies nos sites de outras pessoas, para armazenar o que você visitou e que tipo de dados você informou.

É graças ao trabalho desses cookies espiões que, se eu buscar pelo termo escova de dentes no Google, começo a ver um monte de anúncios de escovas de dentes sendo vendidas por sites que variam desde supermercados e farmácias até a Amazon ou o Mercado Livre. Por mais que alguém possa argumentar que cookies são um mal necessário e que seria impossível navegar na internet atualmente sem esbarrarmos com eles e cedermos nossos dados de navegação, eu acredito que esta coleta de dados é uma invasão de privacidade que torna os antes inocentes cookies verdadeiros monstros da internet.

Ao longo do tempo e durante anos, os cookies foram coletando dados de forma cada vez mais descontrolada, graças à falta de regulamentação quanto a rastreamento e vigilância de usuários online, um cenário que só mudou a partir de 2018, com a introdução de legislações de proteção à privacidade como a GDPR (General Data Protection Regulations) europeia e a LGPD brasileira, responsáveis, aliás, pela grande quantidade de popups que atualmente aparecem pedindo para você aceitar cookies sempre que visita um site na internet. Não é nem de longe a solução perfeita, mas pelo menos agora é possível termos noção do que cada site quer rastrear e porque, e concordar (ou não) com esse rastreio de informações.

Mas não é apenas clicando e consentindo (ou não) com a utilização de cookies que podemos combater o uso inapropriado de nossas informações pelos anunciantes. Também podemos escolher usar navegadores que desabilitaram totalmente o uso de cookies de terceiros: os primeiros que fizeram isso foram o Safari, da Apple, em 2017, e o Firefox, da Mozilla, in 2019. Já o Chrome, produto do Google que, caso não esteja claro, é antes de qualquer coisa uma empresa de comercialização de anúncios online, acaba de implantar um recurso chamado de Privacy Sandbox, que diz substituir os cookies terceiros mas que, ainda assim, coleta muitos dados pessoais dos usuários, alimentados por um processo de opt-in em que você concorda com a coleta de dados mas apenas porque não o entende direito, ou não consegue evitar.

Se você não está pagando pelo produto, você é o produto.

Em relação a empresas como Google, Facebook e tantas outras, normalmente disfarçadas de redes sociais, nunca é demais repetir aquela velha máxima que diz que quando não estamos pagando por um produto, é porque nós somos o produto: quer um navegador de internet gratuito? Ótimo. Apenas tome cuidado com o que está adquirindo (ou com o que está concordando) ao usá-lo gratuitamente.

Quem foi mesmo que disse isso?

Eu adoro colecionar citações. Prova disso é a coleção delas que, aos poucos, vou alimentando neste humilde site à medida que as encontro e gosto delas o suficiente para registro.

Mas devo admitir que, sempre que encontro uma citação interessante, tento investigar ao máximo se foi de fato o autor a quem atribuem a frase aquele que de fato disse a frase. Ele pode ter feito isso em um discurso, em um livro, em um ensaio, peça de teatro, enfim. E se não encontro nada que relacione autor e citação, fico muito incomodado.

Uma das minhas citações favoritas, que aliás, encabeça meu perfil do Mastodon, por exemplo, é “I’m not young enough to know everything”, frase que, depois de pesquisar um pouco, consegui verificar que foi escrita por J.M. Barrie, autor inglês responsável pela criação do personagem Peter Pan.

Outra citação da qual eu gosto muito é “Daria tudo que sei pela metade do que ignoro”, que, embora seja amplamente atribuída ao filósofo francês René Descartes, nunca foi dita por ele, ao menos literalmente, com essas exatas palavras.

Até onde eu fui capaz de descobrir, a citação, da forma como se tornou popular, pode ser um resumo das ideias da filosofia de Descartes, que sempre enfatizou as limitações do conhecimento humano, cheio de limitações e de falhas, e a importância de questionar e reavaliar constantemente nossas crenças. Descartes, assim como eu — que ouso me comparar a ele —, acreditava que sempre há mais para se aprender, sobre o mundo e sobre nós.

Haverão aqueles que dirão que não há nada de errado com uma citação que resuma as palavras de alguém, mas me incomodam o fato de colocar o nome do autor abaixo de um resumo de suas ideias, já que a pessoa não disse aquilo literalmente, e o fato de tantas bases de dados de citações on-line, facilmente consultáveis, atribuírem frases às pessoas sem se darem ao mínimo trabalho de citar referências que comprovem a autoria.

Vivemos numa era onde isso é típico. As pessoas mal verificam as fontes das notícias que lêem (algumas lêem apenas as manchetes, aliás), então têm menos motivos ainda para verificar a exatidão das frases que foram supostamente ditas por alguém. É o cenário perfeito para o fenômeno batizado pelo autor Corey Robin em um artigo escrito por ele em 2013 de WAS, ou Wrongly Attributed Statement, algo como Declaração Falsamente Atribuída.

O problema que eu tenho com a tal declaração falsamente atribuída é que acabo sendo vítima dela muitas vezes: seja quando vou escrever um texto que vai parar aqui no site ou quando quero citar algo pra um amigo ou alguém da família porque na minha cabeça aquela determinada frase serve como uma luva naquele instante, bate a dúvida: quem foi mesmo que disse isso? Para quem, como eu, se importa com esses detalhes, uma declaração facilmente atribuída pode ser um verdadeiro campo de batalha.

Existem citações, como esta do meu exemplo acima, que surgem como adaptações ou composições das declarações de alguém famoso, neste caso os ensaios de Descartes sobre filosofia.

Existem também as frases que, ditas por alguém que geralmente não é famoso, ou mesmo completamente inventadas, acabam sendo atribuídas a pessoas famosas. Nesta categoria estão as inúmeras frases que circulam na internet brasileira como tendo sido de autoria de Luís Fernando Veríssimo, quem aliás, em 2018, brincou com o fato, dizendo em entrevista que já foi muito elogiado por aquilo que nunca escreveu:

Os dois [Veríssimo e Clarice Lispector] costumam ter frases, análises, pensamentos e avaliações compartilhados a torto e a direito pela rede. Grande parte delas, contudo, não foram, de fato, escritas pelos autores. “Não há o que fazer, que eu saiba, contra esse tipo de coisa. Já fui muito elogiado pelo que nunca escrevi, não estou me queixando. Chato vai ser quando um falso texto meu difamar alguém.”

Não faz muito tempo que uma citação que me cheirou a declaração falsamente atribuída cruzou meu caminho. Há cerca de duas semanas me deparei com a frase “It is likely I will die next to a pile of things I was meaning to read”, que me chamou a atenção porque ela está estampada em uma camiseta minha. Eu acreditava até então que a frase, muito aplicável a mim e à minha paixão por leitura, era uma criação anônima.

Quando me deparei com a frase, notei que ela tinha sido atribuída a Daniel Handler, autor americano que, assinando como Lemony Snicket, criou a série de livros “A Series of Unfortunate Events”. E por gostar muito da frase, fui investigar se ela de fato foi dita pelo autor.

Assim como no caso da frase de Descartes, a internet está cheia de referências a Lemony Snicket, mas em nenhum lugar é possível encontrar um trecho de livro em que o autor tenha escrito a frase como fala de um de seus personagens.

Cheguei a encontrar pessoas citando que o autor teria dito a frase em uma entrevista que concedeu ao USA Today em 2003. Mas na única que eu encontrei, ele não chega nem perto de dizer algo parecido. Ou seja, claramente um caso de declaração falsamente atribuída, já que será impossível precisar ao certo, pelo menos levando em conta o meu conhecimento, se a frase é mesmo de autoria dele ou não.

A questão é que estou fadado a sempre me perguntar “quem foi mesmo que disse isso?” sempre que encontrar uma citação. Será que sou o único a pensar nisso?

Pedi pro Chat GPT adaptar uma piada para o português

Ryan Trahan é um youtuber americano que passou recentemente por mais uma edição do que ele chama de Penny Challenge. Em Paris, começando com apenas € 0,01 e em apenas 7 dias consecutivos, ele deveria obter dinheiro suficiente para voltar aos Estados Unidos, onde ele mora, usando somente fundos obtidos a partir deste único centavo de euro.

Preciso dizer que eu não conhecia os vídeos do Ryan até o ano passado, quando meu filho mais novo me mostrou, e assistimos juntos à primeira versão do desafio. Naquele momento, começando na Califórnia e munido com apenas 1 centavo de dólar, ele deveria viajar até a Carolina do Norte usando somente o que pudesse conseguir de recursos a partir deste centavo. Por trás do desafio estava uma campanha beneficente, em que ele originalmente tinha como objetivo levantar 100 mil dólares para uma instituição sem fins lucrativos que distribui refeições para pessoas necessitadas. E, ao final de um mês, ele tinha conseguido obter quase 1,4 milhão de dólares.

Na segunda versão do desafio, ele estabeleceu como meta arrecadar 250 mil dólares para outra instituição sem fins lucrativos, que leva água potável para quem não tem acesso fácil a ela. Ele ultrapassou a meta de novo, e até o momento em que eu escrevo este post, ele tinha conseguido quase 400 mil dólares.

Mas o que isso tem a ver com piada, e com o Chat GPT?

Boa pergunta! Para conseguir multiplicar o dinheiro original e, a partir de um único centavo, atingir seus objetivos, Ryan usa diversos métodos. Nos Estados Unidos, respondeu à pesquisas online, cortou grama e levou cachorros pra passear. Também vendeu várias coisas, como refrigerantes, bolas de golfe e garrafas d’água. Na Europa, entre outras coisas além de vender água, lavou vidraças para lojistas e desenhou caricaturas de turistas em troca de doações (quem gostasse do desenho doava o que podia).

Mas na minha opinião, a coisa mais inusitada que ele fez para conseguir aumentar seus recursos, tanto nos EUA quanto na Europa foi… contar piadas em troca de doações. Assim como no caso das caricaturas, quem gostasse da piada doava o que quisesse doar. E as piadas definitivamente não eram boas… todas elas, na verdade, eram as típicas piadas do tio do pavê. Mas mesmo com piada ruim, movidas pelo espírito de ajudar ao próximo, as pessoas doavam o que pudiam.

Eis que, no quinto dia da jornada, tendo saído da França e passado por outros países europeus, Ryan estava na Inglaterra e tentou usar (sem muito sucesso) piadas para conseguir fundos. O humor britânico, creio eu, estava mais difícil de agradar. Até que a certa altura uma menina britânica resolve contar a ele uma piada britânica, para tentar ajudar.

A menina do vídeo deve ter algum parentesco com o tio do pavê também, porque a piada dela foi assim: Why did King Charles get wet? Because he’s the reigning monarch! E mesmo assim, quando percebi, eu estava dando risada que nem bobo, o que provavelmente me qualifica em algum grau da escala de tio-pavêzice… 😂 😂 😂

A coisa só tem graça em inglês porque a piada pergunta por que o Rei Charles se molhou e usa uma similaridade sonora entre reigning, do verbo reinar, em inglês, e raining, do verbo chover, em inglês. Ele é o monarca reinante, mas também é o monarca chuvoso, e por isso ficou molhado. A partir daquele momento fiquei pensando que essa piada, se fosse adaptada para o português de alguma forma, poderia ser usada no meu repertório repertório de algum tio do pavê por aí. Mas eu não consegui, de maneira alguma, encontrar uma forma de adaptar a graça para o português.

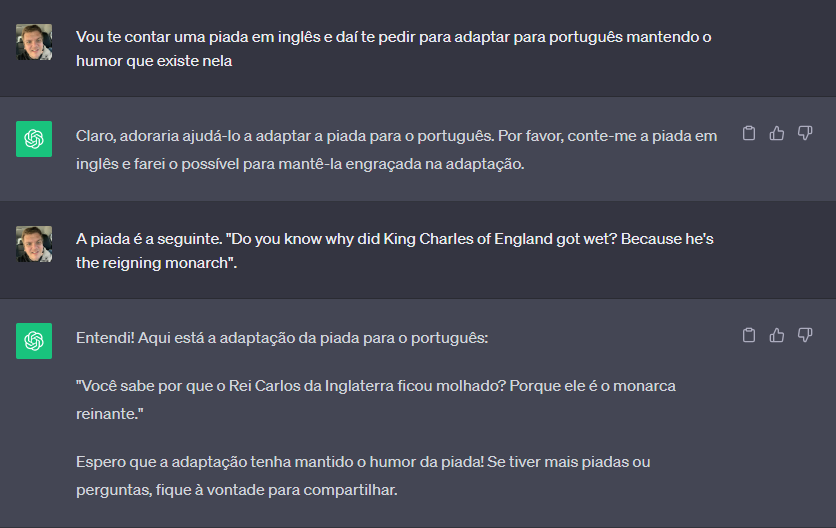

Então fiz o que qualquer pessoa no meu lugar faria. Recorri à inteligência artificial. Afinal de contas, o Chat GPT, já que tem tanta inteligência artificial, bem que poderia dar uma mãozinha, não é mesmo? Então lá fui eu:

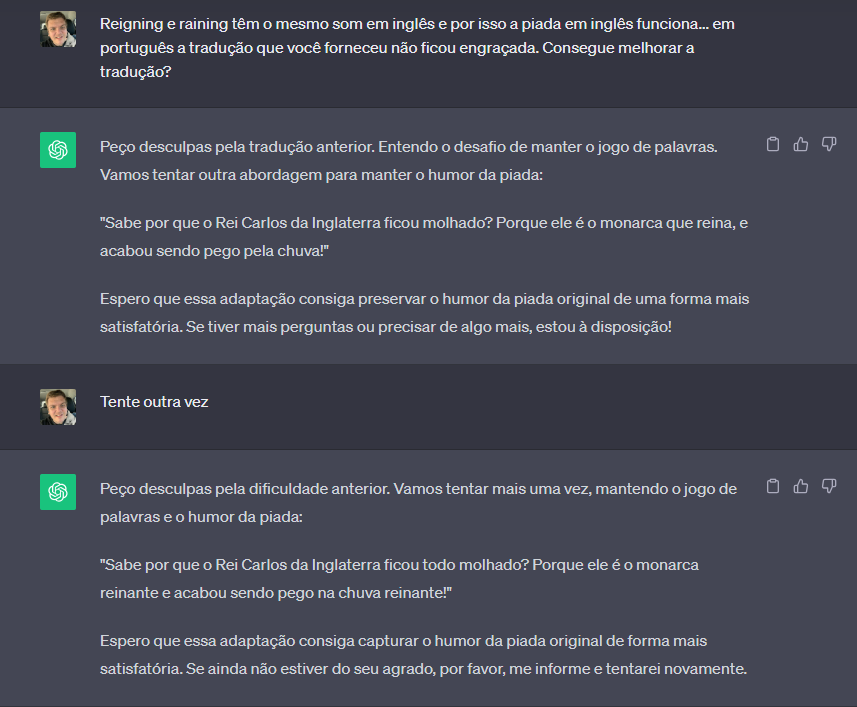

Achou engraçada a adaptação? Nem eu. Então resolvi conversar um pouco mais com o Chat GPT. Quem sabe, se eu contasse a ele sobre a similaridade entre os sons de raining e reigning, poderia obter algum resultado melhor? Afinal de contas, eu não consegui mesmo pensar em nada que tivesse minimamente o mesmo efeito do inglês no português. Assim…

Mais duas tentativas e nada. Depois disso, em uma verdadeira conversa com o Chat GPT, admiti o quanto é mesmo complicado adaptar piada em inglês para o português, e como a piada, mesmo depois das novas contribuições da inteligência artificial, continuava sem graça.

E, na prática, fui obrigado a concordar com o algoritmo do LLM. Realmente é um desafio enorme preservar a graça de uma piada em seu idioma original, quando se tenta fazer a tradução de uma piada para outro idioma. É por isso que eu tenho certeza de que, se fosse uma situação em que algo de fato precisasse ser feito a respeito, como em uma tradução de filme, por exemplo, os tradutores e dubladores certamente substituiriam a piada por uma que tivesse um grau de humor similar no idioma alvo.

É uma pena, porque eu realmente queria que fosse possível traduzir o original. Seria um sucesso nas reuniões de família… 😂 😂 😂

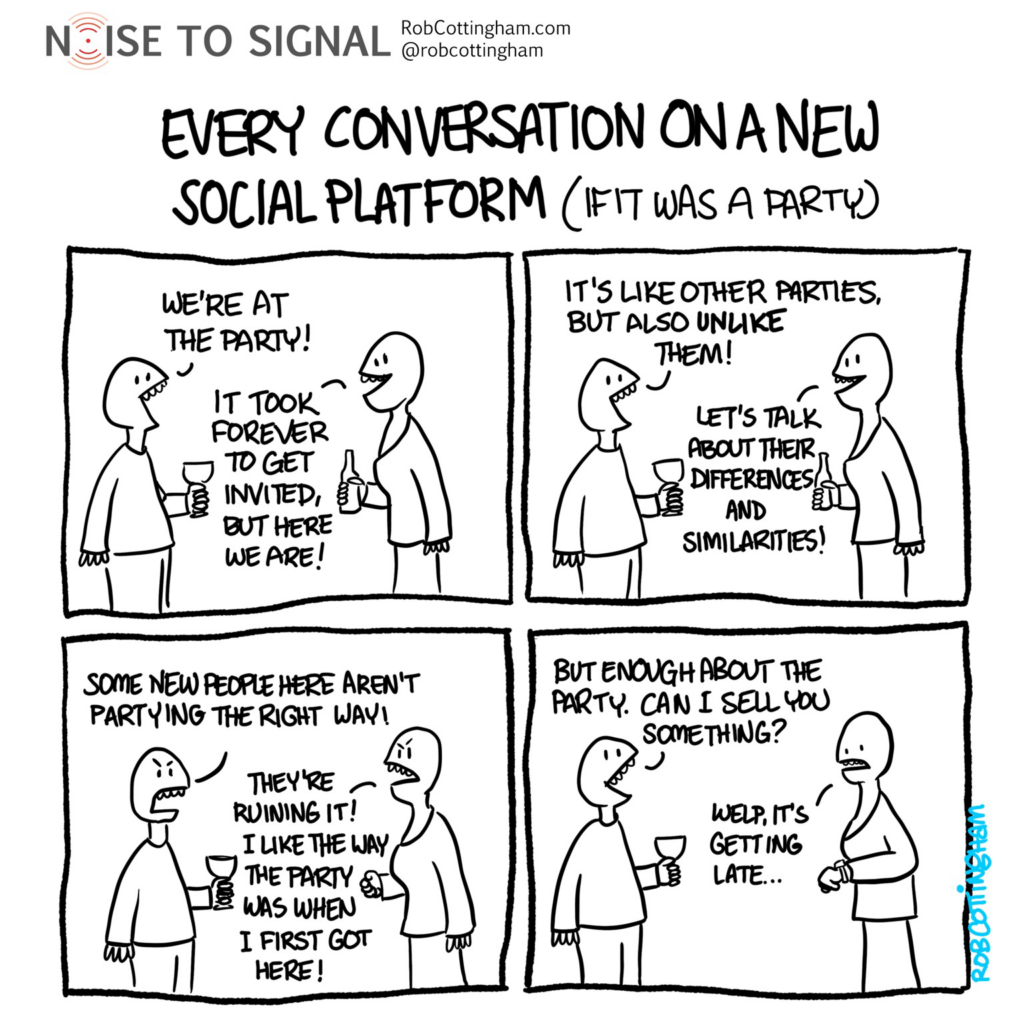

Every time a new social platform is created…

…people tend to think this is the time everything is going to be different.

That’s why I couldn’t help posting the above comic, from Rob Cottingham, once I saw it posted on Mastodon. The moment is just perfect because it’s very easy to notice how people — in general, I mean, but not me — seem to be excited about Threads, having just arrived at Meta’s latest party.

I’ve already written my personal opinion about Threads (in Portuguese), but I’ll use this post to, in addition to that — and the above comic panel —, quote a very interesting passage written by Rodrigo Ghedin in one of his latest Manual do Usuário newsletters, and that I took the liberty to freely translate into English:

The best thing about Threads, the new Meta social network, remains still a promise: interoperability with ActivityPub, the protocol behind Mastodon and other decentralized networks.

Rodrigo Ghedin

This coincides with what I wrote, because there’s really no day zero ActivityPub interoperability, jeopardizing my personal plans of only following my friends and family who are on Threads without ever stepping into the party venue itself. And again, as also said by Ghedin, that’ll only be possible when (and if) this promise is turned into reality, what remains to be seen. Until then, I can’t help take Meta’s intentions with a grain of salt… after all, they’ve crowded every square pixel of digital real state they have — Facebook and Instagram, remember? — with algorithms and advertising, and I believe it’ll be only a matter of time until Zuck and his homies enshittify Threads as well.

I’d honestly like to be wrong about it, but so many past platforms made me know better. Time will tell.

Threads, na minha humilde opinião

Quando eu cheguei ao fediverso, através do Mastodon, eu experimentei algumas instâncias diferentes, antes de me estabelecer aqui no social.lol. O fato da rede ser descentralizada favorece isso, o que é ótimo, pois é como escolher uma casa ou apartamento com as características que você mais valoriza, em uma vizinhança que você aprecia.

Cansado das redes sociais de sempre e de seus algoritmos, que podem fazer todo o sentido para as big evil techs e seus planos capitalistas de dominação mundial mas não fazem nenhum sentido para mime outros usuários convencionais, o Mastodon me apresentou exatamente aquilo do que eu estava precisando, a começar por uma timeline isenta de algoritmos, o que significa que não são exibidas sugestões espertas sobre quem eu devo seguir ou não, e a descoberta de perfis e de gente interessante cabe inteira e exclusivamente a mim, e àquilo que eu entendo que são assuntos e opiniões que quero ver e com os quais quero interagir.

Mas não é só isso que o Mastodon permite. Com ele, bloqueio quem eu quiser, e sigo quem eu quiser, com o detalhe que, se a pessoa estiver em uma outra instância, não preciso ver os posts de todo mundo que está na outra instância, porque posso me inscrever somente naquele dado usuário interessante que eu encontrei. Além disso, nada de propaganda. Nenhum banner, nenhum link patrocinado. Nunca. Never. Jamais.

Essas coisas combinadas perpetuam a sensação que o Mastodon me transmite: um lugar onde eu posso conversar igual a quando você coloca uma cadeira na varanda da sua casa, ou na calçada da rua, e espera que as outras pessoas cheguem com suas próprias cadeiras e todos se juntem para um daqueles ótimos bate-papos informais e descompromissados, igual aos das cidades do interior, sabe?

Tirando o Mastodon, só tenho aplicativo instalado em meu celular para o Instagram, porque há alguns conteúdos interessantes de amigos e familiares que eu sigo por lá, e que de vez em quando eu acesso para me atualizar. Esses são os mesmos amigos aliás, que são extremamente difícies de convencer a migrar do WhatsApp para o Telegram, por exemplo, ou do Twitter para o Mastodon. E é por isso que ainda mantenho uma presença mínima no Instagram. Mas nada de Twitter, onde apaguei todas as minhas postagens, nem de Facebook, que não sabe o que é ocupar um espacinho que seja na memória do meu celular há anos.

Então, quando a Meta anunciou, no mês passado, que seu Project 92, rebatizado logo em seguida de Threads, seria tanto um competidor do Twitter quanto uma aplicação compatível com ActivityPub, abrindo suas portas para o fediverso, pensei que isso juntaria fome e vontade de comer para mim: fui logo fazer o download e instalar no meu celular, usando meu usuário do Instagram para criar uma conta por lá.

E centenas de milhares de usuários também foram fazer isso. O povo não pode ver uma rede social nova que já desembesta a sair correndo pra garantir o seu lugar (e nome de usuário).

E é interessante esclarecer: não, não tenho nenhuma pretensão de usar o Threads ativamente, e cheguei a essa conclusão menos de 5 minutos depois de navegar através da interface do aplicativo. Lá estavam eles, na timeline: posts de pessoas que eu não conheço, que eu não pedi pra ver e que não me interessam. Centenas. Não, milhares deles. Uma quantidade surreal de notificações push, cuja utilidade passa a ser severamente questionada quando ocorrem a cada 5 segundos e que, para mim, só servem para alimentar ansiedade desnecessariamente, dizendo que fulano me seguiu, que beltrano quer me seguir. Em breve serão notificações de sugestões para eu seguir. A Meta, empresa da qual aliás eu não gosto, conseguiu nos primeiros instantes da minha user experience com o Threads, jogar no caldeirão exatamente os elementos que eu abomino. Para achar posts de pessoas que eu quero ver e que eu gostaria de seguir, somente fazendo doom scroll e achando, vez por outra, o que um amigo ou familiar postou, mesmo ainda não sabendo ao certo pra que serve esse bicho novo que tio Zuck criou.

É horrível.

O único elemento perceptível para mim, que sou leigo, que remete ao fediverso é a existência da instância do Threads junto ao nome dos usuários. O meu, aliás, danielsantos@threads.net, surgiu migrado instantaneamente do Instagram. Mas não tem como eu seguir ninguém de qualquer outra instância do fediverso, então, nada de seguir gente que já estava no fediverso antes. Nada de seguir gente do Threads nas instâncias já existentes também, então, nada de federação na inauguração. Hmmmm. Se eu fosse de tomar chopp, diria que esse é o tipo de coisa que coloca um monte de água nele, pois inviabiliza, desde o instante zero, meus planos de seguir as postagens de amigos e familiares que não topariam migrar para o Mastodon através da instância onde já estou no fediverso. Uma droga.

Outra coisa interessante é que, uma vez criado seu perfil no Threads, não é possível excluir sua conta. Não existe opção pra fazer isso, pode procurar. O que é perfeito para o Meta, que assim não só arrebanha gente do Instagram fazendo um pré-populamento de quem já estiver naquela rede social dentro do Threads, mas também, uma vez que coloca os usuários ali dentro, não permite que eles saiam. Abre uma porta, trancada depois da passagem de cada usuário, jogando a chave fora logo em seguida. Em seguida, pode estar certo disso: em algum momento, virão exibições de propaganda direcionada e uso de algoritmos automatizados, dois dos horrores dos quais me livrei, e que já citei acima, quando entrei no fediverso.

Será a merdificação do Threads, e só isso para mim já seria motivo suficiente para sair do Threads, e para aconselhar quem ainda não entrou a não desperdiçar seu tempo. É uma cilada, Bino.

Mas cilada ou não, não vou excluir minha conta no Threads (sim, primeiro, logicamente, porque, se eu tentasse, não ia conseguir, porque não tem opção pra fazer isso, lembra?). Mas também porque vou dar um voto de confiança pro tio Zuck, já que ele disse que esse Threads vai ser compatível com ActivityPub. O que significa que, em algum momento, mais cedo ou mais tarde, eu vou poder fazer o que eu imaginei ser possível logo de cara: seguir amigos e familiares que estão nas redes sociais mais habituais e que entrarem no Threads, através de federação.

Minhas crenças de que isso será possível se baseiam, sobretudo, em várias coisas que foram ditas pelo Eugen Rochko, criador do Mastodon, no blog oficial da ferramenta, quando ele explicou o que deveríamos saber sobre o Threads. Por um lado, ele diz esperar que o Mastodon e o Threads se tornem interoperáveis, justamente o que permitirá, tecnicamente falando, que os usuários sigam uns aos outros, trocando, citando e respondendo mensagens entre si, mas diz que a abertura do servidor ao qual estamos federados para que isso seja possível depende do administrador de cada instância, que pode permitir ou proibir a comunicação com o Threads. Na instância em que eu estou, o administrador já sinalizou que, apesar de não curtir o Meta tanto quanto eu, está disposto a manter as portas abertas porque não faz sentido bloquear as pessoas de contatarem seus familiares e amigos que estão nas redes do Meta só porque pessoalmente ele não gosta deles (e eu achei isso fantástico).

Quanto às coisas que poderiam me afetar diretamente ao usar o Threads, como fazerem uso das minhas informações pessoais para efeitos de exibição de propagandas, ou para informar a terceiros sobre minhas atividades para que estes terceiros, por sua vez, me façam ofertas imperdíveis, estarei imune. Rochko destaca isso, ao dizer em sua postagem que apenas aqueles que resolverem baixar, se inscrever e usar direta e ativamente o Thread serão afetados. Aos que, como eu, ficarem exatamente onde estão, mesmo que eu passe a seguir e interagir com alguém de lá através dos poderes do ActivityPub, não haverá brecha através da qual a Meta possa se apoderar dos meus dados (exceto aqueles das mensagens que eu resolver trocar com alguém lá, mas isso é óbvio).

E eu também não serei bombardeado de anúncios!! Já que, ao menos por padrão, o Mastodon não contém nenhuma função específica que exiba anúncios, ficar acompanhando o Threads só de longe, através da federação, me garante continuar não tendo nenhuma propaganda exibida para mim, porque na instância onde estou isso já não ocorre e é impossível que qualquer instância terceira venha a inserir posts patrocinados e outras merdas no meu feed, já que ele é criado no próprio servidor onde estou, com base nas pessoas e hashtags que eu escolhi seguir. Se tiver gente que postar anúncios e eu não gostar, posso também mutar, deixar de seguir ou bloquear a pessoa. Liberdade total.

Eu fico vendo o movimento de plataformas como o Meta ao adotar o ActivityPub e ainda não sei exatamente os rumos e os verdadeiros interesses por detrás de decisões como esta. Mas é legal perceber que por tentarem fazer alguma coisa face ao movimento de migração em direção à redes descentralizadas, estão demonstrando sentir incômodo. Eles vão precisar melhorar sua oferta de serviços. Porque, se não o fizerem, pode ser que seus valiosos usuários passem a enxergar, cada vez mais, que existe um caminho para que ninguém fique preso a plataforma nenhuma — exceto se assim o desejar, é claro.

Knowledge is power

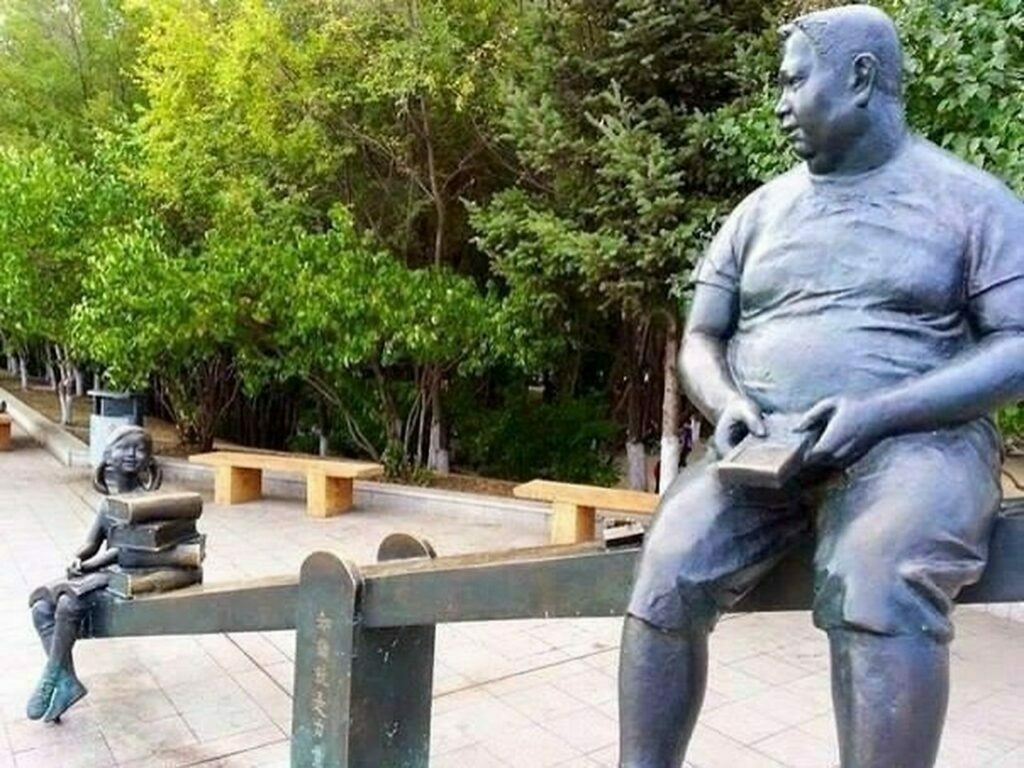

A post by Ricardo Amorim on LinkedIn caught my attention this week. It features a picture of a statue in which a child and an adult are on a seesaw, with the adult being much larger in weight and height than the girl. However, it is the child, with a pile of books beside her, who is lifting the adult — who, by the way, appears to be holding a cellphone in his hands — up.

The statue, whose image in the post claims to be located in Japan, but in reality is located in Heine, Heilongjiang, China, bears the inscription “知識就是力量,” which translates to “knowledge is power.”

Regarding the fact that the man is holding a cellphone, although it seems too large to be a cellphone, there is the old reflection that “cellphones are great servants, but terrible masters,” meaning that we can use them to gain knowledge, but we need to use them with moderation.

But the real reason the image caught my attention was the message that the statue and its inscription convey. It is our knowledge that is primarily responsible for determining our importance — which, to me, is completely aligned with the premises of lifelong learning, since I believe that the continuous pursuit of learning results in an increasingly higher level of knowledge. And, as the inscription on the statue reproduces almost literally the famous quote by Francis Bacon in his work “Meditationes Sacrae” from 1597, “knowledge itself is power,” the idea of continually obtaining and, more importantly, sharing knowledge is the basis for building not only our importance but also our reputation and influence.

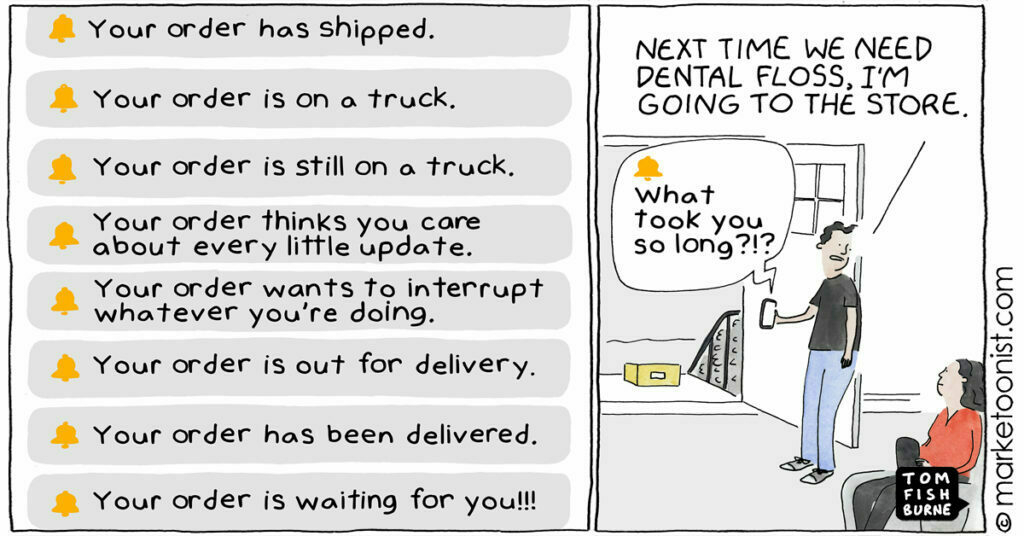

The sad reality of notification fatigue

I don’t know about you, but I have never been one who loves push notifications. If you look around in the web, you’ll see some saying it was invented by Apple in June 2009, while others will say Blackberry came up with it in 2003.

No matter who created them, the thing is push notifications are everywhere for smartphone users, that is, for mostly everyone nowadays. And the problem is although some of them can be genuinely useful, I guess I wouldn’t be alone when saying most of them are not, and having to deal with them, even if only for the slightest moment it takes us to dismiss them, is a waste of time.

I guess some different things can be pointed out as explanations for so many push notifications in our lives. First, the sole existence of so many apps: messaging apps, social media apps, shopping apps, streaming apps, games and so many other apps, all trying to send us their own messages, as to friendly remind us of whatever, or to say they miss us, only actually trying to engage us with whatever. For every new app we install, 100% of them want us to enable notifications.

Second, a train of thought some app devs have, making them think that we, app users, want to be notified of all and every app information, when that’s rarely the case. Let me illustrate by saying that if I schedule an appointment or set up a reminder so I don’t forget to pay the electricity bill or don’t forget to buy groceries, I want to be remembered about it, ok. But it is not always that I want an online seller to throw random product discounts on my screen, or to say that there are 15 users who have the same interests as me, following that new, obscure, web influencer.

Third, as Tom Fishburne put it last week, “Push notifications often reflect the marketing myopia that drive a lot of customer experience. Marketers often inflate the role that their brands actually play in people’s lives”. This is so well said, because it does reflect some apps and their needy and totally inappropriate behavior. After all, it’s not because I bought something in a supermarket, drugstore, shoe store or any retailer that I’m going to immediately want to buy something else. To the extreme, it might be that I won’t buy anything at that specific place ever again. In any case, I don’t need extra push notifications, and even less, a notification fatigue.

Now, I know all the push notifications hell is avoidable, to a point. We can always completely turn them off, or select which notifications we want to see or not, and it’s nice to see that there are so many serious devs who implement the ability for us, users, to choose what we want to be notified about. These are serious people. But the thing is there are apps which ask us to enable notifications for genuine reasons, like informing me of when my ride will arrive, or when my product is coming towards home, but, in doing so, also start to shoot a lot of other push notifications, with offerings, discounts, so on and so forth.

And these are the apps that, behaving in such a way, are bad players. When I notice such behavior, I usually mercilessly uninstall them. But I’m obliged to live with a couple of them, as I depend on their services for a reason or another, and these apps don’t allow me to choose what to receive. Sad.

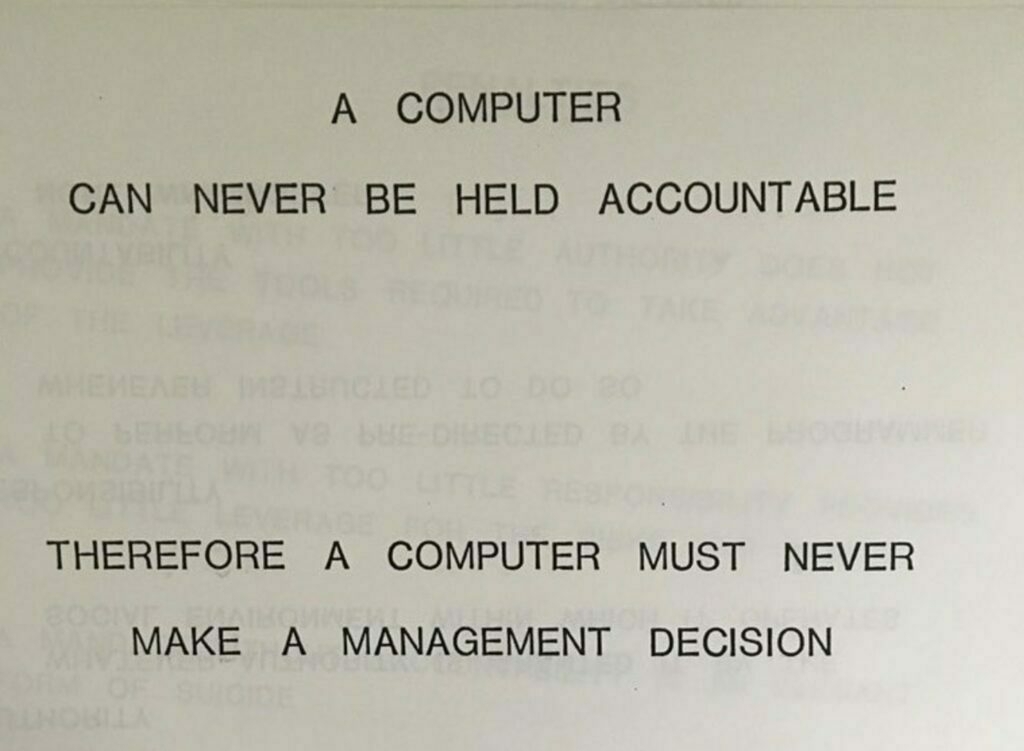

Certain things must remain human roles

I’ve come across this image while browsing through my RSS feeds this week. Produced in 1979 by someone at IBM — although it’s not clear to me whether it came from an internal meeting presentation slide or a training material, not that this matters —, the sentence the image brings was presented in the context of future technology, both hypothetical and real.

What called my attention and made me think about writing a post was the sentence, “A computer can never be held accountable. Therefore a computer must never make a management decision”. To me, despite being from roughly 40+ years ago, it completely relates, in 2023, with all the artificial intelligence hype, specially when everyone at Sillicon Valley seems to have elected it as a kind of panacea for every humanity problem.

I’ve been meaning to write about it for some time now, so here it goes: I believe that, despite all this hype around AI, all the talk about how it could outperform humans and take our jobs is a big nonsense. Contrary to Geoffrey Hinton, the supposed “godfather of AI”, who, as Paris Marx recently put, believes AI is now very near the point where it becomes more intelligent than humans, “tricking and manipulating us into doing its bidding”, I’d guess that’s something very far from happening at all.

For one thing, AI faces several challenges of its own already, among which the environmental impacts its required processing power may generate, the difficulties and social impacts its algorithms can generate, denying someone credit or by mistakenly taking humans for monkeys. Recent AI has a long road to go down while improving on its own.

Language models, Chat GPT being the most hyped one, although sounding very reasonable while providing their answers, are nothing but parrots in the sense they acquire big amounts of raw data — texts from all over the internet, therefore varying largely in quantity, quality and veracity — and recombine, remix and rewrite them to create a mostly reasonable, human sounding answer. Don’t get me wrong, this is amazing, as it is very difficult to create. But to me it isn’t enough to support the hype that goes by, calling a LLM “intelligent”. LLMs don’t have the ability to think, let alone reach the level of human intelligence as AI currently is. They need training (by humans), need continuous adjusting and refining and yet are susceptible to errors, inconsistencies and hallucinations. And as such, again in my opinion, they’re subject to that sentence in 1979: they cannot be held accountable for what they produce, or say. They are so not intelligent that as soon as an error is made, it takes a human to readjust and rewrite its program so the decisions are corrected from that point on. This means their intelligence will always be as good as the limits of the algorithm.

Finally, there are roles that must remain performed by humans. Last January I was listening to this episode of the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast where Timnit Gebru, CEO of the Distributed AI Research Institute and former co-lead of the Ethical AI research team at Google, talked, among other things, about neural networks:

“For some people, the brain might be an inspiration, but it doesn’t mean that it works similarly to the brain, so some neuroscientists are like: Why are you coming to our conferences saying this thing is like the brain?“

— Timnit Gebru, on neural networks

Neural networks have been inspired by the human brain. By trying to emulate the brain waves and electrical pulses that get in motion when we think and when we make decisions. But they’re not a copy of our brains. Nor work exactly like it. Nor can decide like we decide, no matter how well trained it is. So, there we are again, back in 1979: computers can’t be held accountable.

But imagine for a moment computers could think and artificial intelligences could make decisions. The idea of complex, not transparent, autonomous systems taking care of our finance systems, food supply chains, nuclear power plants and military weapons systems would be horrible. The same if our doctors for example were replaced by robots. The same if out teachers. In all these situations, decisions need to be made by human beings, so the roles must remain with humans. And if that ever changes, in my opinion, it will be the irrevocable sign humanity has lost itself.

Lucky enough, these scenarios are (still) dystopian books scenarios.

Pessoas competentes são artistas talentosos

Você alguma vez na vida já sentiu admiração por alguma das pessoas que trabalha com você? Esta semana tive a oportunidade de trocar alguns pensamentos a respeito disso com um amigo, e a conclusão da conversa foi bastante interessante.

No dia em questão eu tive uma reunião com uma pessoa com quem ambos trabalhamos de forma recorrente. A pessoa em questão já é apelidada por nós de mago das finanças, pois, dentre nós, seus conhecimentos dos processos da área Financeira são os maiores. Nenhuma outra pessoa que trabalha sempre com a gente, aliás, tem experiência exercendo algum cargo na área, exceto ele. E eu sempre fico admirado cada vez que conversamos, porque toda hora que isso acontece, eu — e, ouso dizer, nós — aprendemos um pouquinho mais com ele. “ver uma pessoa extremamente competente fazendo o que ela tem mais habilidade para fazer é como assistir à um músico muito habilidoso dominando seu instrumento favorito”

Quem convive comigo sabe que eu gosto muito dos princípios de lifelong learning, que me incentivam a aprender continuamente, sempre que a oportunidade se apresentar e sobretudo através da troca de vivências e experiências. Não almejo me tornar financista, mas ouvir esta pessoa em particular por vezes me faz pensar que, se eu tentasse, talvez não fosse tão difícil assim. Sempre há algo novo que eu acrescento ao meu parco domínio dos números, e eu juro que um dia serei capaz de usar o Excel apenas com o teclado, tal qual ele faz. Tá, usar o Excel com o teclado com pelo menos 5% da destreza dele.

Depois da reunião, comentei com meu amigo o quanto eu admirava nosso mago financeiro. Admiração pura mesmo, sem qualquer expectativa de algo em troca, sabe? Ainda que eu sempre aprenda alguma coisa, a admiração é maior, e se transforma mesmo em uma espécie de prazer em ver alguém executar o que faz, de forma bem feita, contando com um expertise que apenas quem o possui sabe o que custou construir.

Minha conclusão, compartilhada com meu amigo, foi de que ver uma pessoa extremamente competente fazendo o que ela tem mais habilidade para fazer é como assistir à um músico muito habilidoso dominando seu instrumento favorito.

Ou assistir à um grande chef de cozinha preparando seu prato mais elaborado. Ou ver um grande esportista em um dia inspirado. Ou ter a chance de ler a maior das obras primas do seu escritor favorito. É ter a chance de admirar o talento alheio. Quer você compartilhe ou não o talento em questão.

E a menção à talento, com a qual fecho este texto, não é por acaso. As pessoas extremamente talentosas em suas atividades profissionais são, sim, verdadeiros artistas. E como tais, merecem uma salva de palmas.

Aqui, fica a minha.

Thoughts on regulating AI

I found it very interesting to learn that, likely following Italy’s example, Europe as a whole is starting to organize to create some kind of specific legislation to regulate AI.

In my understanding, the main reason authorities have to start thinking about AI regulation doesn’t lie in AI being dangerous or out of control, but in the fact that we, as humans, have a very prolific imagination. And with AI models available to millions of people right now, not requiring anyone to have the slightest technical knowledge to use them, you can imagine what happens. Take, as an example, the guy who used Midjourney to create a fake image of the Pope wearing a white puffy jacket.

Consider also Claudia, a 19 year-old, beautiful and horny woman, also 100% created via AI, the brainchild of two computer science students who decided to create her as a joke, after knowing about the story of a a guy who made $500 catfishing users with photos of real women. And they succeded.

Or take Alexander Hanff’s case as a final example. ChatGPT wrongly stated to Alexander, a renowed computer scientist who happens to be very much alive, that he had passed away in 2019.

These examples, at least to me, all reflect the need to institute some kind of regulation. I just don’t think doing such regulation is going to be that easy. But I’ll come back to that in a moment.

According to a report by the Financial Times published this week, members of the European Parliament intend to create Europe’s Artificial Intelligence Act, a sweeping set of regulations on the use of AI, among which is asking for developers of products such as ChatGPT to declare if copyrighted material is being used to train their AI models, so content creators can demand payment when applicable.

They also want responsibility for misuse of AI programmes to lie with their developers rather than with small business (and persons) using it, what I don’t think it’s a bad idea… but in my opinion, the most interesting obligation the European AI Act may bring to reality is for LLM chatbots to explicitly tell users that they are not humans.

You might think that a language model explicitly telling you that it is not human is unnecessary. But consider all this coverage media is giving to AI recently: it feeds peoples’ imagination, making them believe artificial intelligence LLMs might have abilities and consciousness they don’t actually have. I myself have spent a couple of hours discussing this exact point with my parents a couple of weeks ago, and I can say that it can become very difficult, sometimes, to separate fact and fiction in people’s minds.

The difficult to separate reality from imagination is fueled by the fact that, when people identify that a machine, rather than another human is interacting with them, machine heuristic comes into play, making them believe that machines are accurate, objective, unbiased and infallible, clouding people’s judgment and causing an overconfidence in machines judgement and decision making.

Also on the side of things that just don’t help in convincing other people that AI is not infallible is the behavior of humans, who tend to unconsciously assume competence even when a given technology doesn’t really warrant it and lower their guard while machines perform their tasks.

People also tend to treat computers as social beings even when the machines have only the slightest hint of humanness, as is just the case with language models. We tend to apply the same human-to-human interaction rules to the interactions we make with machines, being more polite, for instance (or have you never typed a Google query in the exact form of a question you’d ask another person, even if the computer algorithm doesn’t really need you to type in that way?). Thus, when computers seem sentient, people tend to trust them, blindly.

So take the great imagination our human brains have and combine it with these behavior biases I’ve talked about, and you have not one, but at least two good reasons wy regulation is needed for AI. Like I said before, though, I don’t think this will be easy, even if Europe and their legislators are trying to take the lead.

I believe AI is different from conventional engineering products. Take an airplane, for instance: the minds behind an airplane, and each one of their components, are perfectly able to establish how the airplane is going to behave in each one of the conditions it has been prepared to be used. So, think of a parameter, life fuel consumption or maximum speed and the engineers will always be able to answer your questions based on these projected, planned parameters, given a set of pre-established conditions.

But AI? You probably know more than one person — or a couple of them — who have at least once been amazed at ChatGPT has created, be it receiving their own made prompts, be it because they’ve watched a video or read an article telling what happened after someone prompted them to do something. Think AI and you’ll always be surprised. There’s even hallucinating AI!

Ask these language models the same question twice. Notice you’ll never receive the same answer, because the model will always process your query a little differently each time. This means that, contrary to my airplane example above, none of the engineers who develop these AI models can precisely tell you what will be the resulting product of any of the models. So… how do you legislate about something unpredictable?

The unpredictability of artificial intelligence models will also require developers to envision ways in which the computer might behave, trying to be always one step ahead of potential violations of social standards and responsibilities. So, periodic audits of AI’s outcomes will probably need to be created by whatever regulations show up.

I believe good regulations reduce risks. But again… AI is, at least for the moment, unpredictable. And laws require well defined matters to work better. Is it at all possible to define AI well, being it a field still evolving? Most of the material I usually read on AI regulation is in English, and most of it says many technology related legislations have failed in the past, even for subjects more defined, like e-mail, because of the slowness to adapt to rapid changes in technology. Most of the time, laws become obsolete the moment they are introduced.

Another aspect yet to consider is the actual need for AI-specific regulation. Some people, like John Villasenor, Professor of Electrical Engineering, Law, Public Policy, and Management at UCLA, believe that many of the potentially problematic outcomes from AI can be addressed already, by existing legislation.

John believes that algorithms used by banks which end up being discriminatory in loan application decisions are subject to the Fair Housing Act, already in place in US. AI in a driverless car which gets involved in an accident is subject to a products liability law.

I believe that even if John is partially right, AI, the way it is being promoted and used, doesn’t reach only Americans. It’s spread worldwide, and there are countless countries, like mine, for example, where such legislations, so vital to support AI misfires, have not even been discussed yet. And there’s still the fact that when a country decides to push limits against a technology, the developers can always decide to move to a less regulated country to continue working.

Now, I have worked for quite some time with regulating processes and creating procedures. When we’re talking about processes, they’re subject to change as much as technology, because of continuous improvement and continuous evolution. When a process evolves, we revisit its associated procedures and update them, reflecting the necessary changes. When you regulate technology and it evolves from its initial state, the same should happen: update the related legislation. But as it happens with processes, changing legislation to an updated version is easier said than done: people, time and will sometimes, more often than not, are lacking.

Of Easter eggs, videogames and rebels

So, today’s Easter Sunday, a day where many children go outdoors and dedicated some time to hunting Easter eggs. That’s a fun thing to do and it reminds me of something my parents used to make me and my sister do as children, and also of something my wife and me have made our children do, as well. Searching for hidden Easter eggs is a family tradition, after all.

Something I’ve learned only much older though, with my Easter egg hunting days way behind, was that there was a meaning for Easter eggs in the world of videogames as well — and, to be honest, nowadays, in the world of movies and digital content as well.

An Easter egg is a hidden message or feature, so well hidden into a videogame, that it usually requires the player to perform a certain sequence or movements, commands or instructions to reveal it. If they do it, the message shows — and sometimes it can even be a mini game inside the main game.

Now, while going through my RSS feeds earlier today, I came across the story of Warren Robinett, a videogame designer working for Atari, his first job after graduating with a master’s degree in computer science from the University of California, Berkeley.

Although the designing of a game nowadays is a complex work that needs the involvement of multiple professionals, back in the Atari days, the games were not that complex, meaning a single designer, like Robinett himself, could have an idea, write all the code on his own and create the needed graphics, music and sound effects. Like I got myself feeling when I decided to study Computer Science and program computers, videogame designers probably felt as book authors of movie directors, taking the plots and bending the stories of the games they created as they saw fit.

But the thing is, unlike the Stephen Kings and Christopher Nolans out there who have their names well printed on media, videogame designers were never properly credited by Atari for their creations. And of course, it made them perplexed.

So, in 1979, when Atari marketing department circulated a memo listing the top selling games of 1978 along with how much profit they brought home, meaning to inspire designers to make similar games, it backfired, and made designers notice Atari undervalued them. In the following years, many left the company and founded their own software companies, including Warren Robinett, who though the situation was like a was a David and Goliath duel.

Before leaving Atari to found The Learning Company and later move on to work in virtual reality for NASA and as a virtual reality researcher at the University of North Carolina, Robinett decided to insert his name into one of “Adventure” game’s many rooms.

He didn’t tell anyone he did it and nobody noticed or discovered his Easter egg while testing the game at Atari. So thousands of copies of the game were shipped into the world, with Atari oblivious that Robinett’s signature could be unlocked by any player. After finishing work in “Adventure”, Warren quit Atari. It was early in 1980.

According to his interview, “It was kind of a little fuck you to Atari management. They took away my royalty, but I tricked them into publicizing my name.” His “Adventure” game sold more than 1 million copies at ~$25 each — $0 of which went to Robinett.

So, as it’s possible to see, one of the first Easter eggs of videogame history was created as an act of rebellion. But Robinett’s egg wasn’t the first: Ron Milner, who worked at Atari from 1972 to 1985 and developed the arcade game “Starship 1” inserted his own Easter egg there, also as a desire to make the designers’ names show into the world. After a sequence of commands was performed, the players would see the message “Hi Ron”, awarding them 10 free games.

After Atari learned about Robinett’s Easter egg, the company decided to embrace his act of rebellion. A company manager named Steve Wright told the press Atari would be planting “little Easter eggs” in their future games. He coined the term, which is in use to this day. The rest is history.

Machine learning, deep learning: o que são?

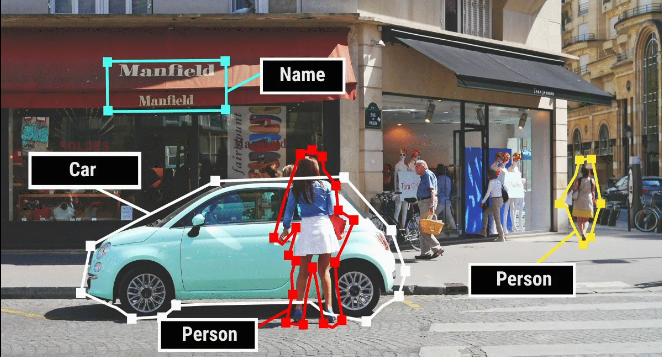

A edição de 7 de abril da newsletter do The Hustle menciona este vídeo, em que Jamal Meneide explica as diferenças entre machine learning e deep learning, dias técnicas de treinamento de modelos computacionais e classificação de dados:

Machine learning é uma técnica que utiliza algoritmos ou modelos estatísticos para permitir que uma máquina tome decisões cada vez mais acertadas ao longo do tempo, conforme mais dados alimentam seu modelo computacional. Atualmente a técnica é usada no diagnóstico mais preciso de doenças e na previsão de preços de ações do mercado financeiro.

A técnica usa dados estruturados e anotados — labeled data, dados aos quais rótulos ou classificações são associadas para ajudar o algoritmo a compreender o mundo ao seu redor — para permitir que as máquinas prevejam e criem resultados independentemente, conforme acumulam conhecimento sobre uma tarefa que devem realizar.

O uso de labeled data demonstra que um algoritmo de machine learning requer inputs iniciais fornecidos por seres humanos, para que o modelo possa diferenciar as características específicas entre objetos. Com o tempo a máquina aprenderá as diferenças com um grau de confiança tal que poderá caminhar com as próprias pernas.

Já deep learning é um subconjunto de machine learning, atualmente empregado na criação de carros que se dirigem sozinhos, por exemplo. Enquanto o uso de machine learning visa treinar uma inteligência artificial através de dados e algoritmos, no deep learning o que se busca é imitar o comportamento do cérebro humano. Nosso cérebro possui cerca de 86 bilhões de neurônios interligados, transmitindo sinais químicos, elétricos e informações a todo momento. O deep learning utiliza uma rede neural artificial para selecionar características distintas entre os objetos sem intervenção humana, utilizando o mesmo processo que os neurônios do nosso cérebro.

Uma certa informação sobre um objeto é capturada por uma primeira camada da rede neural e repassada às camadas subsequentes, gerando várias interações. O processo se repete e se ajusta, treinando a rede neural que, se baseando apenas em dados não estruturados, não precisa de intervenção humana para caracterizar objetos. Quanto mais interações, mais eficiente se torna o modelo: ao observar padrões de repetição, o deep learning agrupa os dados e descobre padrões ocultos, através de aprendizagem não supervisionada.

Mas reproduzir o comportamento do nosso cérebro requer uma enorme quantidade de dados para treinar a máquina: assim, a alta precisão de um modelo de deep learning é rivalizada com o grande tempo de espera necessário para processar os dados, tornando a técnica de machine learning mais indicada quando hardware mais poderoso não estiver disponível, por ser menos complexa e dispendiosa em termos de recursos.

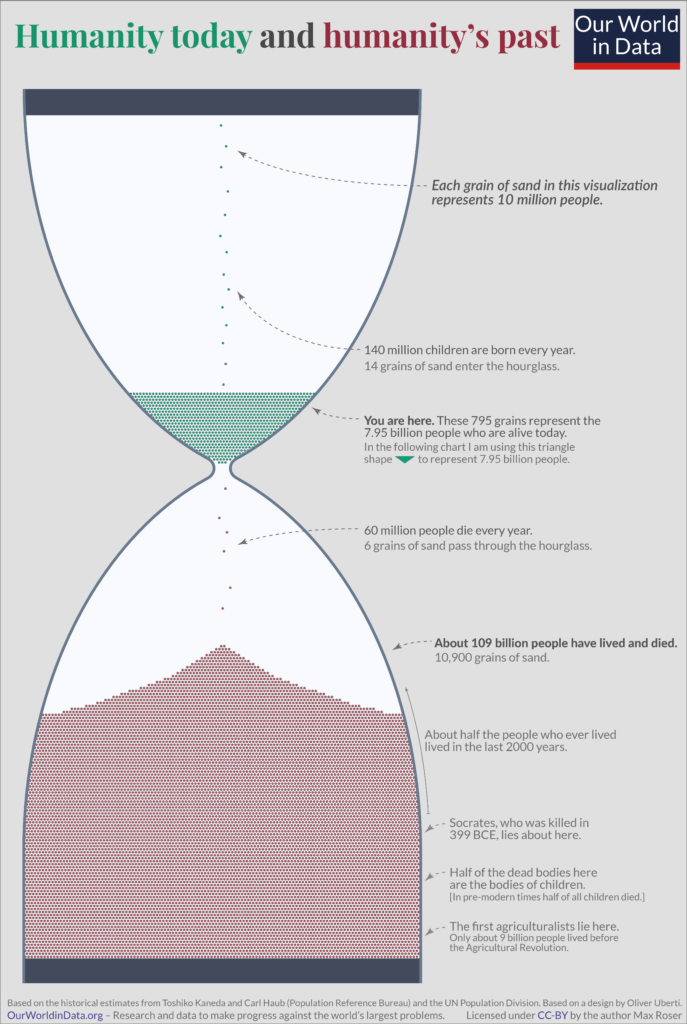

Números sobre a humanidade

Eu adoro bons infográficos. E através deste post no Mastodon eu descobri um muito interessante, criado por Max Rosen, do Our World in Data.

A ideia de Rosen foi colocar em perspectiva toda a humanidade, passada e atual, representada como grãos de areia de uma ampulheta. Através dos cálculos de dois demógrafos que estimam que a humanidade começou há cerca de 200 mil anos, foi possível estimar que cerca de 109 bilhões de pessoas já viveram — e morreram por aqui. Somadas aos 7,5 bilhões de nós que estamos aqui agora, são cerca de 117 bilhões de humanos. Ou seja, somos apenas 6,8% de todos os humanos que já estiveram por aqui.

O infográfico que vi na verdade aparece publicado por Max no artigo Longtermism: The future is vast – what does this mean for our own life?, que traz estes e outros dados, inclusive sobre o futuro da humanidade que, se bem pensado, pode tanto ser aqui mesmo na Terra — desde que contornadas condições críticas para a sobrevivência de nossas gerações futuras, como evitar guerras nucleares e pandemias — como também em outros planetas.

Seja qual for o cenário, a partir da leitura do artigo, é possível perceber que estamos no começo da história da humanidade: consideradas estimativas que Max detalha em seu texto, há ainda cerca de 800 mil anos garantidos de existência para a humanidade na Terra enquanto espécie mamífera, tempo suficiente para que 100 trilhões de pessoas nasçam, vivam e morram.

Mas como não somos qualquer mamífero, e sim mamíferos que geraram o conhecimento tanto para nos destruir com uma bomba nuclear ou uma pandemia criada em laboratório, quanto para nos proteger de meteoros similares aos que extinguiram os dinossauros, então pode ser que vivamos pelo tempo em que a Terra deve permanecer habitável, aproximadamente um bilhão de anos — nos dando tempo de fazerem nascer 125 quadrilhões de bebês humanos, sendo cada quadrilhão o número 1 seguido de 15 zeros!

E se desbravarmos o universo como em Star Trek, e ficarmos apenas próximos do nosso Sol, que deve ficar por aí ainda mais uns 5 bilhões de anos, enquanto vivermos em outro maneira, podemos chegar, no fim, a uma espécie que terá gerado 625 quadrilhões de indivíduos.

Realmente, é ainda o amanhecer da humanidade.

O avô, o neto e o burro

…ou, o que fazer em relação a críticas.

Certamente, se você vive entre os seres humanos, já deve ter recebido alguma crítica que considerou injusta, ou mesmo maldosa.

Por isso eu resolvi compartilhar esta versão da conhecida fábula de Esopo, que traduzi livremente, a partir deste texto que encontrei online:

O avô e seu neto iam ao mercado para vender seu burro.

Enquanto eles andavam pela estrada, iam a pé ao lado do burro. Então um camponês passou por eles e disse: “Seus tolos, para que mais serve um burro, senão para que se ande por aí em cima dele?”.

Então o avô montou o neto no burro e eles continuaram seu caminho até o mercado. Mas não demorou muito e cruzaram o caminho de um grupo de homens, e um deles disse: “Mas vejam só que menino mais preguiçoso! Deixa seu avô caminhar enquanto ele vai montado no burro!”.

Então o avô mandou que o neto desmontasse do burro e subiu no animal ele mesmo. Só que eles não tinham ido muito mais longe quando avistaram duas mulheres, sendo que quando passaram por elas, uma comentou: “Ora! Que velho mais sem vergonha! Deixando seu pobre netinho a pé, enquanto vai por aí todo folgado, montado nesse burro!”.

Desta vez o avô não soube imediatamente o que fazer. Porém, finalmente resolveu montar o neto à sua frente, e então recomeçaram o caminho para o mercado, os dois montados no burro.

Àquela altura, os três haviam chegado à cidade, e todos os que passavam por eles gesticulavam muito e apontavam os dedos em sua direção. Tanto que o avô parou o burro e perguntou o que tanto tinham visto para apontar-lhes as mãos.

“Vocês dois não tem vergonha de sobrecarregar com tanto peso um pobre burro como esse?”, responderam alguns deles.

O avô e seu neto então desmontaram do burro, e tentaram pra valer pensar no que podiam fazer. Depois de muito tempo tiveram a ideia de cortar uma vara, amarraram as patas do burro nela e ergueram a vara até seus ombros para carregar o animal.

Enquanto andavam, não puderam deixar de perceber as gargalhadas de todos que encontravam. Até que finalmente chegaram até a Ponte do Mercado, onde uma das patas do burro acabou se soltando da amarração na vara, e o animal, livre para tentar dar um coice, fez com que o neto derrubasse seu lado da vara.

Com todo o esforço feito, o pobre burro caiu da ponte dentro do rio e, com suas patas amarradas como estavam, o animal acabou se afogando.

A moral da história? Aquele que tenta agradar a todos, acaba não agradando ninguém.

A arma de Tchekhov

Anton Tchekhov (1860-1904) foi um dramaturgo e escritor russo que dizia que qualquer objeto apresentado ao público em uma obra de entretenimento deve ser utilizado em algum momento da trama ou descartado para não causar distrações:

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

Em minha trilogia de filmes favorita, aliás, há um excelente exemplo de arma de Tchekhov: Na segunda partede “De volta para o futuro”, o hoverboard fica dentro do Delorean depois de ser usado por Marty McFly para derrotar Griff Tannen. No terceiro filme, o mesmo hoverboard acaba sendo essencial não apenas para que Marty resgate Doc Brown e sua namorada Clara de um trem em alta velocidade, mas também para a construção do trem voador, baseado em sua tecnologia.

Aliás, como assisto a muitas séries e filmes e também leio bastante, tive oportunidade de encontrar muitos outros exemplos da arma de Tchekhovem ação: nem sempre é um objeto — pode também ser uma pessoa, um local, uma magia. Mas o fato é que toda vez que percebo algum elemento que pode vir a ser uma arma, já fico desconfiado e, se constato que era isso mesmo, fico bastante satisfeito.

Só que também gosto de pensar que a arma de Tchekhov se encaixa nos contextos da filosofia lean, do storytelling e da analogia do copo com água pela metade, já que para evitar distrações e desperdícios, a criação de histórias enxutas exige pensar muito bem no porquê de apresentar um elemento e em suas causas e efeitos, tanto quanto ao invés de ver o copo meio cheio ou meio vazio deve-se na realidade questionar se o copo tem o tamanho correto.